What’s your favorite item on the menu? (I’ve learned not to ask what’s best on the menu because you get some version of, “they’re all good.” And if you ask for the best seller, you get a variety of the restaurant’s “specialty,” or “known for,” or “they’re all good,” but with a qualifier of “I probably sell more of.” Asking a server for their personal favorite elicits a personal response.)

I’ve tried everything on the menu, and I like the lasagna best. It is a little more Mediterranean than other lasagnas, which I like.

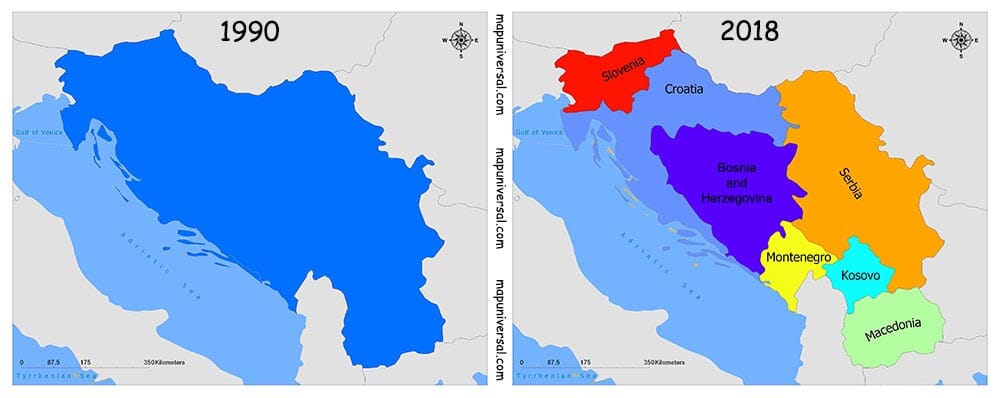

I asked how it compared to another entrée I was considering. It’s very good, and he proceeded to compare the two entrées including why he still preferred the lasagna.Gabe’s accent was eastern European, and he was quite personable, so I asked. He’s an Albanian refugee. His family immigrated when he was a child during the wars in the 1990s as part of the breakup of Yugoslavia. I learned, too, that the owner was an Albanian refugee and a friend of the server’s father.

Our server seemed tentative in telling us he was a refugee of the civil war. Perhaps he was concerned which side we would come down on. Seeing that we were impartial, interested, and empathetic to him on a personal level, he added a little more explanation before leaving for another table.

Reflecting later on the young man’s refugee status, I arrived at the disappointing realization of just how little I knew about the conflict. Of course, I recall the conflict, but honestly, I didn’t pay attention to the what or why of it. If anything, I was mildly frustrated by the changing names of post-Soviet countries. (So much for that old globe I have!)

I wondered about our son’s Bosnian friend in high school. Was he a refugee whose family fled the war? In a demonstration of my inability to decipher languages, (if it wasn’t English or French, it must be Spanish!), I was picking up my son after tennis practice one sunny afternoon. As my son was getting into the car, a mother got out of the car next to me and called out in a foreign language to let her son know she was there. I asked my son, That’s not Spanish, is it? He looked at me and replied, Dad, that’s Bosnian. His implication was clear: You dumbass – don’t you know Bosnian when you hear it?!

Gabe’s status as an Albanian refugee resonated with me with a note of familiarity. Part of our metropolitan area has a high concentration of Croatians. We have friends who grew up in the area, one of Croatian descent and the other Slovakian.

One time in New Orleans we met the woman who owns a great restaurant – if you have the opportunity, be sure to eat at Drago’s. (Even if you don’t like oysters, try their charbroiled oysters. Oh my God! Our son was a teen when he ate there, and he had become a rather picky eater, so of course oysters would be worse than poison. As we raved about them, he finally asked to try one; then he asked if he could get his own order.) Other than having a mutual friend who took us to eat at Drago’s, we learned that the owner was Croatian and knew people in our metro’s Croatian area, whom she visited a couple of times a year.

Our server, Gabe, our friends who grew up in the Croatian area in town, my son’s Bosnian high school friend . . . my curiosity prompted me to do some cursory research. In my casual reading, I consistently found references to the Ottoman Empire – an empire of which I knew very little. Being more than a little curious now, I turned to The Columbia History of the World, a “brief” tome of nearly 1,200 pages . . . and it doesn’t even cover the past 50 years!

The Ottoman Empire grew in a manner similar to the Roman Empire, by conquering neighboring lands in an outward pattern. As The Columbia History begins, “In the second half of the thirteenth century the shattered lands of Anatolia seemed a singularly unsuitable locale for the rise of a new world empire.” (p.604). As they began their expansion, “the Ottomans turned first to the West, where they could exploit the enthusiasm they aroused for the holy war and the quarrels of Byzantine and Balkan rulers.” (pp. 604-7)

The next three centuries saw numerous Ottoman victories: “defeat of the Serbs” (1371); “first battle of Kossovo” (1389); “defeat of the Christian ‘Crusade’” (1444); “second battle of Kossovo” (1448); “capture of Constantinople” (1453); “capture of Cairo” (1517); “defeat of the Hungarians” (1526); to name a few. Near the end of the 17th century, however, the Ottoman’s governing structure began to collapse under its own weight, and their fortunes turned: “capture of Azov by Peter the Great” (1696); “Russian annexation of the Crimea” (1783); “Russian annexation of Georgia” (1801); “Serbian revolt” (1804); and “Crimean War” (1853-56). (Full timeline, pp. 605-6)

I included The Crusades because they are commonly referred to in histories of Western Civilization. Multiple Crusades attempted to capture the Holy Land from Muslim rule. Interestingly, the attempt to allow religious law to coexist with administrative rule of the government contributed to the weakening of the Ottoman Empire: “A radical transformation of the government was theoretically possible through the assimilation of the new regulations to governmental kunans or decrees authorized by Muslim tradition, but as long as the sacred Shariat remained the law of the land, two mutually hostile systems were forced into uneasy coexistence.” (p.617)

I selected the other conquests and losses because of their magnitude, and mostly because of their association with the Baltic and Russian states. Among them: Serbia, Kosovo, Hungary, Crimea, Georgia, and Azov (a small sea flanked on one side by Russia and the other side by Ukraine, with a narrow strait between Crimea and Turkey that moved into the Black Sea; Mariupol in Ukraine is a major port located on the Azov Sea).

(An interesting side note is that the term Potemkin Villages originated as a consequence of the Crimean War. Following the annexation of Crimea into what Russia referred to as “New Russia,” Grigory Potemkin was appointed Governor of the area. When the Russian Empress Catherine II decided to visit to show interest to the people in the area, Potemkin built facades of buildings along the route to create villages for the Empress to visit; the “villages’ people” worked for Potemkin. Once Catherine II’s visit at one village concluded, and she and her court would continue to the next village, the facades would be moved to the next stop on her journey. Historians have mostly determined that the story is at best partially true, but the term Potemkin, referring to a false front, has persisted to this day, in politics and on Hollywood sets.)

Currently, we are three months into the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Speculations for the reason behind the invasion abound, from Putin’s concern over further encroachment by the NATO alliance to Putin’s mental state. One theory that seemed particularly interesting was Putin’s desire to return Russia to some historical level of greatness, signified by moving Ukraine back into the fold. One of his early premises dealt with liberating Russians from the oppressive Ukraine; ironically, one of Potemkin’s objectives was to attract Russians to Ukraine to force assimilation of Ukrainians into the Russian state.

News videos show refugees fleeing, often with little more than the clothes on their backs, carrying their children and even a few dogs. All of this as more apartment buildings, and even a maternity hospital, are being targeted and bombed by the Russians. Regardless of Putin’s reasons, the war is displacing millions of refugees. European Union heads of state are attempting to find ways to accommodate the massive, unexpected influx of Ukrainians. The United States initially committed to allow 100,000 Ukrainian refugees with families in the US to immigrate to the country.

I recently had the good fortune to meet an uplifting man who survived the Holocaust. Our server, Gabe, was a refugee from Albania. I wonder how many more people with whom I have crossed paths also are refugees. I wonder if any of them would say they aren’t better off. I wonder when I’ll get to know the next Gabe.

The lasagna, by the way, was quite good.